“What’s your story?” It’s a big question but one that Elon University and the surrounding community is tackling in deep and meaningful ways.

In 2022, Elon University received a $3,500 grant from North Carolina Humanities to help with the collection and sharing of oral and written histories from African American community members. Elon University students ran intergenerational workshops where they also participated as storytellers, curators, and discussion leaders for the youth and senior citizens attending. Seeing the transformational and healing power of this work, Elon University was awarded a second, larger grant from North Carolina Humanities in 2023 to collect and share more stories. This ongoing community dialogue between younger community members and older community members is building bridges across racial, religious, geographic, and generational divisions and is creating spaces for understanding, healing, and action. You can visit their YouTube channel to witness some of these stories.

We connected with Danielle Lake, the director of Design Thinking and an associate professor in Human Service Studies at Elon, Sandy Marshall, an associate professor of Geography at Elon, and James Shields, the manager of the African-American Cultural Arts & History Center, to learn more about the power of story and place.

How did this project begin?

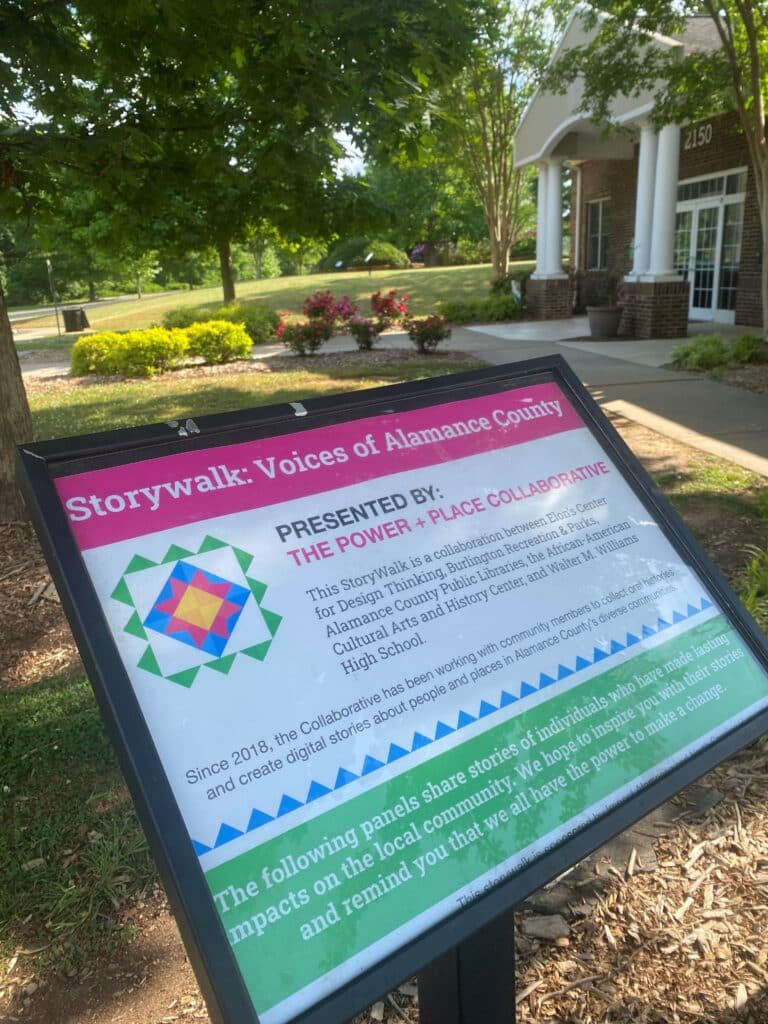

Sandy: We see this work as not only documenting hidden histories, but also bridging communities through the process of oral history gathering and storytelling. The project began as a collaboration between my “Power, Place and Memory” geography class, and the late Jane Sellers, who was the founding director of the African-American Cultural Arts & History Center. I had designed a course at Elon looking at controversies about public commemoration and memorials as a way to learn more about local history. Jane was already doing this work through pop-up exhibits at local libraries and walking and driving tours of predominantly African-American neighborhoods in East Burlington. One day Jane and I were talking about the power of digital storytelling and oral history collection, and we came up with a plan that involved students interviewing members of the community about their memories. Sadly, Jane passed away not too long after our initial pilot project. Her daughter Shanice took over; Danielle joined the staff at Elon; we kept the project going. Now, several years later, we are happy to be working with North Carolina Humanities. In this latest iteration of the project, we are collecting oral histories with the connecting theme of place-based religious diversity. Spaces of faith have been identified as important places of action and change in the community. Working with historically Black churches, rural churches, Latino-serving institutions, the local mosque, and others, we are trying to capture stories of that diversity.

How is respect and trust built as students collect these personal stories and memories from community members?

Danielle: This work begins at the community level. Community members and community partners will share what their values are, who might want to be interviewed, and the stories that have been left untold. We do walking tours and community meet and greets to create opportunities to build relationships between students and the community. I think the intergenerational connections made through this project are so meaningful. We’re not just engaging university students though. We are also working with local schools and summer youth camps.

Sandy: There is magic in people sharing their stories. First, we help students reflect on their own stories by engaging in autobiographical digital storytelling. That way, when it’s time to go into the community and work with others, they can do so with empathy and understanding. After our community storytellers are identified, we bring the students and other community partners together during place-based visits so they can get to know each other. After a few visits students will sit down with their community storyteller and conduct an oral history interview that is recorded on video. Once the story has been read over by the storyteller, the students get images from their storyteller, from the museum, and elsewhere to bring the stories to life in a dynamic, digital way. At the end of the semester, we have a public screening where each student introduces their storyteller and we have a community discussion about the stories. I’m always impressed how there are threads of connection between the individual stories and the community. People say, “Ah, this resonates with me; this is similar to my experience.” Or people will say, “I had no idea this was happening.” This work surfaces memories, but also contemporary issues, and so it becomes a valuable public forum for discussion.

Why do you think oral history collection is important? Why should we document community stories?

James: In African-American culture, a lot of the history is oral. For years oral history has not been as respected as written history by some, but within African-American communities, oral history is very trusted. Because this program is so relationship-based, many people have been happy to share their stories. I think what has really struck me is that people tell stories that have been traumatic for them. For example, one woman shares her story about being a little girl and asking her father to take her to the carousel at the city park, which was a white park. She shares her hurt in thinking “Why won’t dad take me to this park?” She did not know that he wouldn’t take her because of their skin color. That’s something that sat with her for a long time. We must reconcile ourselves with this history before we can move forward. When you know about someone’s story, you begin to have empathy. We just want to recognize one another as humans here in Alamance County. Elon is now a true community partner, not just an institution located in the community. Building community is something we all want, but how do you do it? I think this project is a good way to do it.

What other partnerships have come about through this project?

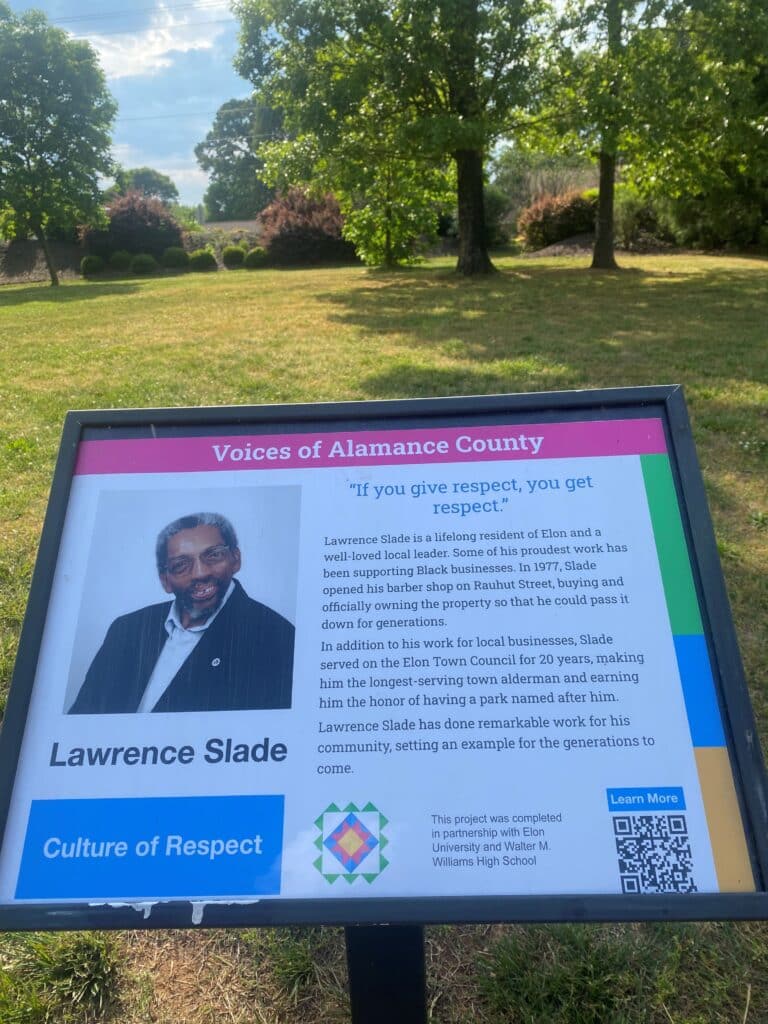

Danielle: We’ve built strong partnerships with many public spaces across the county including with Burlington Parks and Recreation. Alamance County Public Libraries is also deeply supportive, and we are currently working with them now to create story walks!

Sandy: North Park and the Rauhut Street neighborhood were some of our first community partners. We centered some of our community meet and greet walking tours there because those locations were important black business districts that had been displaced and relocated from downtown Burlington. Today, we’re also working with the CityGate Dream Center and the Burlington Masjid. We want to create space for all the many diverse stories that are in our community, including migrant stories and immigrant stories.

James: This project has been crucial to the African-American Cultural Arts & History Center as we have been able to expand our audience. People have come by saying, “I heard that my grandmother was featured in one of the stories, so I wanted to come see that.” People will visit the center now and ask to see our exhibits about the high schools, where they can go through and look at the yearbooks and connect with people of the past. There is a sense of recognition and validation that has really come about through this project.

How can people support this work?

Danielle: You can stay up to date with the Collaborative by visiting our website: https://www.elon.edu/u/elon-by-design/about/power-and-place-collaborative/. Please also visit our Omeka site to access a complete list of materials and resources!

About North Carolina Humanities’ Grantee Spotlights: NC Humanities’ Grantee Spotlights shine a light on the incredible work of our grantee partners, offering details about their funded project, and feature a Q&A with a team member(s) associated with the organization. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.